The following is the text of a talk I gave at the inaugural SupConf last month in San Francisco. The talk itself varied a bit from my notes, but the core ideas are below. The video will be available later and in the meantime I wanted to share the talk and slides.

I want to talk today about the next steps you can take for your career in support. As part of that I’m going to share things I’ve learned over the last 10 years as I’ve built my own career.

To get started, I want to briefly share my own career path. I started working in support while in college. There I worked in an on-campus video production lab. Going into college I knew that I needed a job to cover expenses. It wasn’t an interest in support that drew me to that job, it was necessity combined with the appeal of getting paid to tinker with and learn technology.

It was there that I started using WordPress, which led me to working with the student newspaper. That connected me with a group of students across the country who were all fundmentally dissatisfied with the software available their campus newspapers. Most schools relied upon a limited, proprietary CMS. The group of us banded together and ran a company called CoPress that did WordPress hosting and support for student newspapers. I was the Hosting Director there and it was my real introduction to support. I worked with clients to get their sites set up and help train their newsrooms in how to use WordPress.

All that work with WordPress led me to apply at Automattic, where I started as a Happiness Engineer in 2010. When I joined the support team was around 8 people and we covered email support for WordPress.com. Since 2010 I’ve worked as a team lead, led our support hiring process, and now lead our 150-person support organization. And we’ve expanded to cover support for a half dozen different products across live chat, email, forums, and social media.

But that’s just my career. I also want to talk about what your career in support means at a high level. Because a career in support is a wonderful thing. Support at its heart is about helping people. A career in support means a lifetime of service. It means helping people use your product. Because if you’re not helping people use your product, why are you building it in the first place?

The opportunity exists for your career in support to mean many things. Do you want to build and manage a team? That can be your career in support. Do you want to genuinely teach people every day for many years? That can be your career in support. Do you want to perfect your writing skills and convey technical information in a way people can relate to? That can be your career in support. Do you want to understand how hospitality improves the financial health of a business? That can be your career in support.

And I think that’s why you’re here today. You know that support is more than answering questions all day. Support is a craft that takes time to master. Support as a career means concerning yourself with all aspects of the customer’s experience. You have to look at all aspects of the experience because support doesn’t stop when you hit reply.

In support you are the human connection to a company and its product. For many customers the support team is the company. You may be the only employee a customer really knows. And you may be the only employees who really know your customers. Your relationships with customers provide an opportunity to influence your company at a very foundational level.

So if support has all this opportunity why do we need a conference about how to build a career? If your career can be all of those things, then why are we here? Why don’t we see a burgeoning trend of people clamoring to land support jobs? And why is support still seen as something that’s just entry-level and a dead-end?

The answer to all of those questions starts with recognizing that SupConf, and this community, are special.

Let me ask you something. When you tell people you work in customer support do you think they picture SupConf? When you tell family and friends that you’re headed to a customer support conference do you think they imagine the environment of the last two days?

Because I’ll bet they don’t. I’ll bet what they picture looks a lot more like that room than the atmosphere in here.

When I first started working at Automattic I’d meet people who asked what I did. I’d say that I worked at Automattic where we make WordPress.com and see their eyes light up with interest. “Oh, what do you do there?” they’d ask. When I said I worked on the customer support team more often than not I’d be met with an…

“Oh…” which sapped all questions from their brain.

After a couple times of that happening, though, I realized that it’s not their fault. Their reaction was understandable because much of the world is not like us; we’re not the predominant norm. Much of the short-sighted thinking characteristic of big business doesn’t share our view of support. That doesn’t mean those companies and those people are wrong. It means we have work to do.

We have work to do because that world sees support as nothing but a cost center. That world sees support as a dead-end job. That world compensates support as if anyone can do it. And that world puts nothing into career opportunities because, let’s be honest, who in their right mind wants to make support a career?

We do. But there’s no guarantee that the work we love becomes a viable career path. What we’re talking about here is whether the career we all want becomes the industry norm. The more that happens the healthier and deeper our career paths are.

So if we want to improve this, what’s the work we have to do? We have to first acknowledge that building support as a viable and thriving career path won’t be easy. It’s going to require taking initiative and demonstrating our value to other teams in our companies. More often than not there won’t be existing career systems in place for us to build upon. We need to lay that foundation and share what we learn with others.

There are a couple pieces that I think can help us lay this foundation.

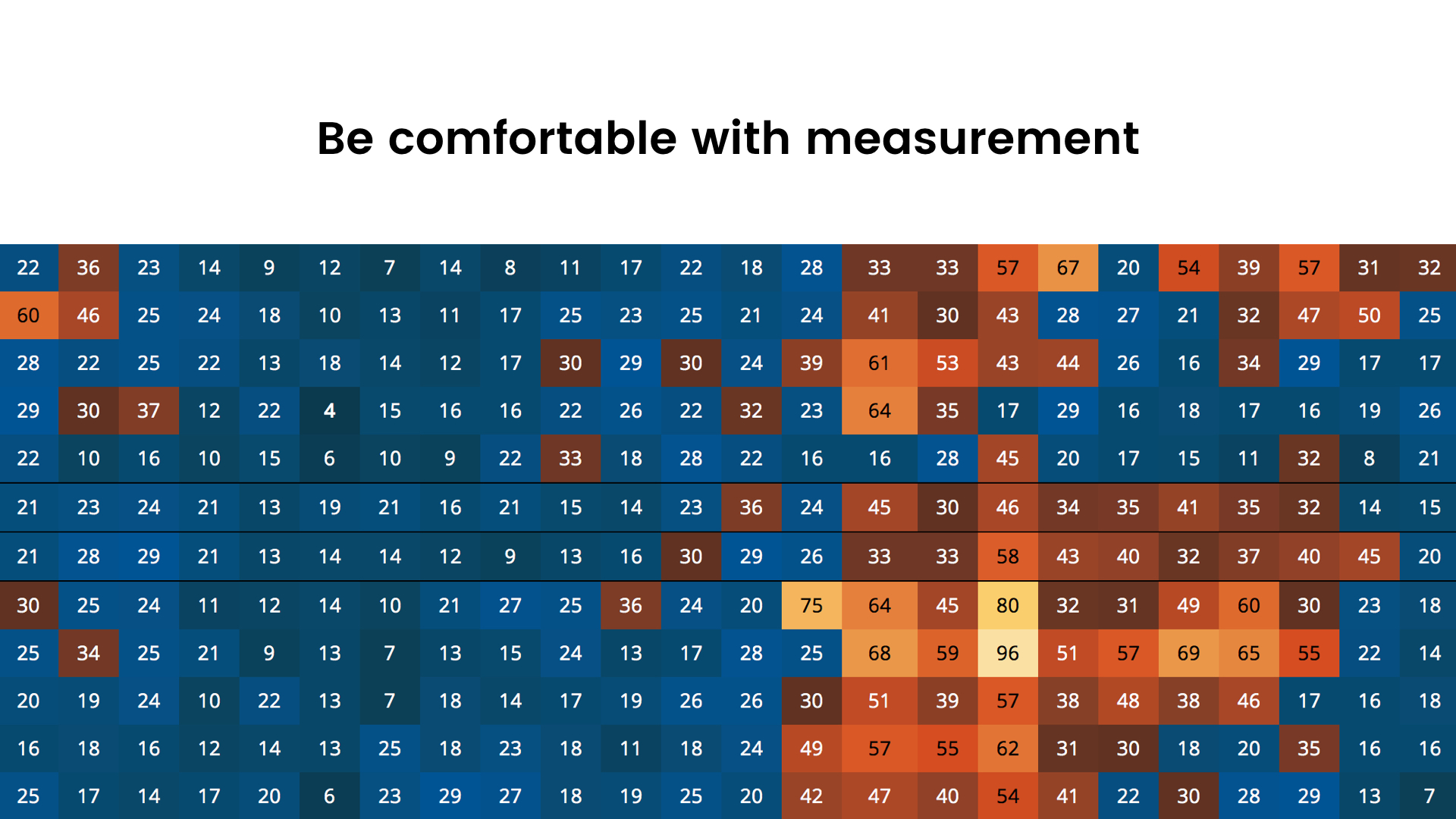

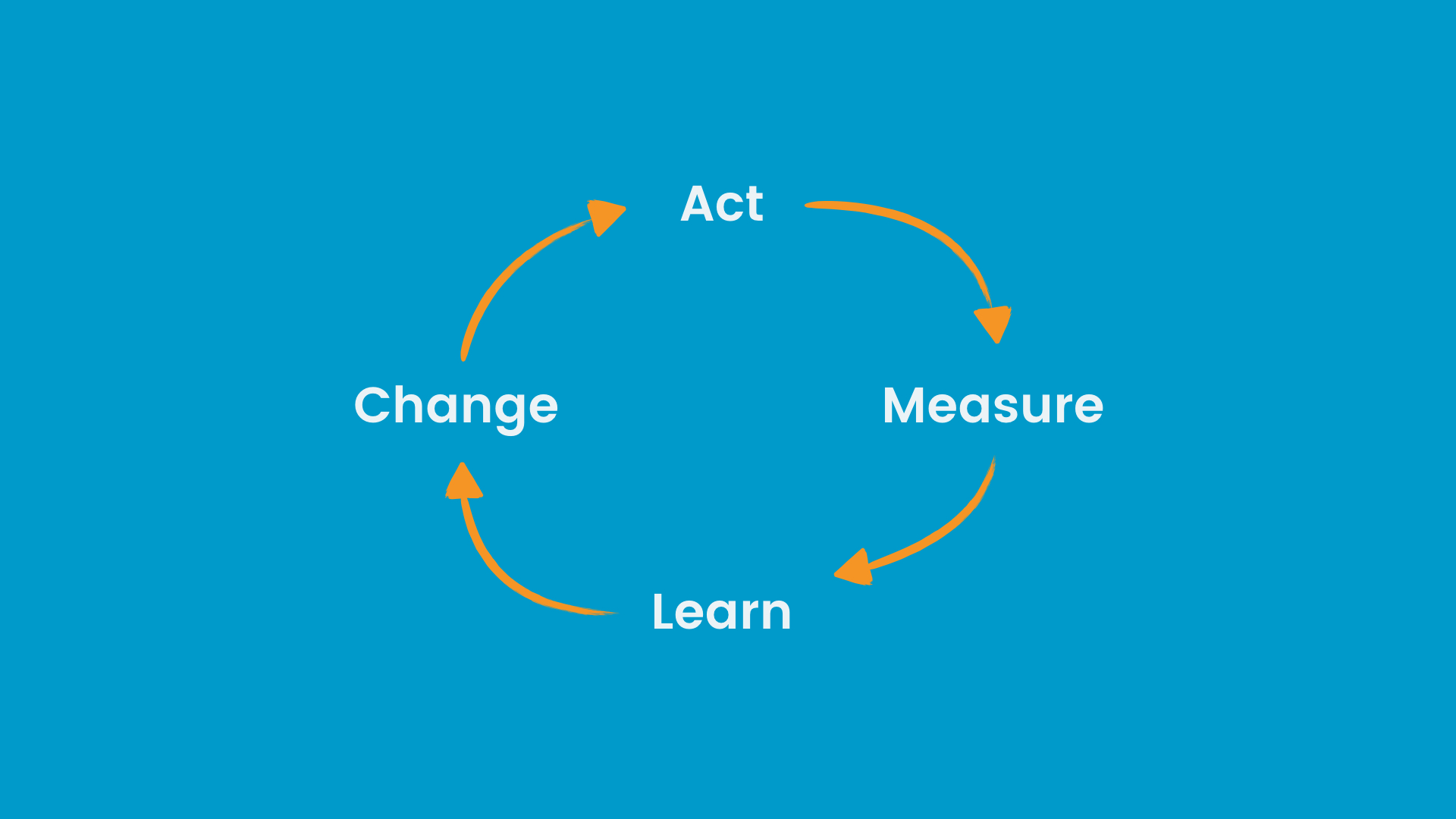

We first need to be comfortable measuring ourselves. And we need to be comfortable tying metrics to company goals and priorities. If we can do that we can start adding value across the company. And we can actively combat the notion that support’s just a cost center.

We need to understand that many aspects of our work can, and more importantly should, be measured.

This doesn’t mean we have to become dogmatic, though. And it doesn’t mean we have to become Comcast. Please don’t build your company to be Comcast, one of them is enough for the world. What we need to do is seek out healthy metrics for ourselves and our teams and then hold ourselves accountable.

When it comes to healthy metrics having a strong perspective helps. On WordPress.com our core focus right now is 24/5 live chat coverage. That’s a highly measurable goal that we need to inform with metrics. We need to look at how many Happiness Engineers we have online, when customers need to chat, how many customers we’re missing in chat, and what our overall coverage is like. Those are all directly measurable things.

But that metric is right for our goal for our customers. You should find what works for your team. Set goals that are relevant to your customers and your business. Your perspective on what works for your team is vital, maintain that. If your team does live chat don’t measure yourself against our 24/5 goal, instead hold yourself accountable to what’s reasonable for your team and your company. When you lose that perspective you risk demoralizing your team and creating misaligned incentives for your customers.

We need to build our support teams to add value across the company. We’re all expert communicators. We know not just the ins-and-outs of our product but how to convey our expertise in a way that’s relatable to our customers. That’s an immensely valuable skill. Our next step must be communicating back to the company what we learn from customers and from each other.

It’s that next step where we all too often come up short in support. We’re great at communicating with customers but, at times, terrible communicating internally to other teams at our companies. How many times do you hear about a development team not being on the same page with support? Or a sales team that makes promises to customers which support knows they can’t do? Those are real problems. And while they’re hard problems they’re solved with clear, consistent communication across teams. That’s our specialty!

Measurable goals, a healthy perspective, and building value across our company are all great things. In most cases, though, you’re not going to find a pre-existing company structure here that builds a path for support to follow. The initiative for defining that path is on you. When it comes down to it you have to own your career. Be proactive, because no one is going to build this for you.

Those are all some things we can do to improve our careers. You can get to a successful career in support. It’s out there. I want to share some stories, more failures than successes, from my own experience to help explain some of this.

One of the things I’ve learned in my career relates to the importance of measurable results that I mentioned earlier. When I started leading a team I was blind to the role goals and measurable results played for a growing team. I say a growing team in particular as when you have 4 people joining every few weeks that means you have 4 people asking questions like: How do I know if I’ve had a successful day at work? What’s the kind of impact our team looks to have with customers? What’s the type of impact our team looks to have in our company? When there are no key measures in place you’ll end up with those new people asking 5 people that question and hearing 5 different answers.

For me, I’d written goals off as too formal and corporate. They’re not. Measurable results are a key piece for communicating the value of our work. It’s important to start this work early, too, as if you’re like me you’ll likely do it terribly at first. When I first started setting goals for the team I looked more at what other companies were doing than where we were as a company. I lost the perspective of what was relevant for our company and our customers. That set us back as a team because our effectiveness is not always about getting more done; many times it’s simply about getting the right things done.

At one point we had a backlog of 5,000 tickets and response times of over a week. And I’d talk about how our goal was to get below 5 hours. 5 hours?! Ha! When you’re 5,000 tickets deep a 5-hour response time goal is about as helpful as wishing you had a magic wand. It sounds great, but just isn’t going to happen.

Another core piece to a successful career is pride. Remember earlier when I told people I worked in support only to be met by their blank stares and raised eyebrows? Well, I have an admission. After a couple times of doing that I started saying I was a Happiness Engineer. That’s the title much of our support team uses at Automattic. The word “engineer” would pique their curiosity in a way that support just didn’t. It let me fake it by talking about how the role also involved new feature testing, bug reports, documentation, and more. It’s not that the role didn’t include those things; it did and still does. It’s that I didn’t feel a sense of pride in owning the fact that I worked directly with customers.

It wasn’t until I realized there were people like Chase, Jeff, Scott, Christa, and others out there that I felt comfortable owning support as my thing. I’d hear Chase talking about his deli job on SupportOps and realize that customer support was a legitimate lens for your work and expertise. He’d relate lessons from the deli to how he helped customers at Basecamp. Food service was also my first job and I’d relate easily to those deli anecdotes. Once I found those commonalities it became much easier to seek out help, advice, and build resources to accelerate my career.

I realized that a strong community was there to support my career. The more I contributed the more I felt comfortable asking others for help and advice. By proactively taking part in discussions, writing blog posts, and sharing how our team does things I was able to build connections that I now draw upon to help me solve problems our team confronts. Being active in a community like Support Driven is the best way we can all support each other.

So what should you do next? Let me recap today by highlighting the three qualities I’d like you to take away from this. I think these form the foundation for a career mindset.

First, you need to be proactive. Your career is like a well-tended garden. If you’re not proactively given it attention and care then it’ll just be a bunch of weeds. On the work side this means taking your career into your hands. Is there a skill you’ve always wanted to learn? Then start; don’t wait for your company to tell you it’s ok. Is there a part of your product that customers hate? Then improve it; talk with customers and communicate with other teams in a language they understand. On the social side: the relationships you build will form the network that propels your career forward. Build and maintain those in a way that’s comfortable for you. At the end of the day it’s your career.

Second, you need to maintain a healthy perspective. Doing this will accelerate your own career progress. Measure yourself by how far you’ve come, not by how you fall short against others. Basecamp didn’t get to 5-minute response times overnight; they put in the work over many years. Your team can do the same. When you’re just starting out the gap between you and others doesn’t mean you’re behind or worse than another. And if you’re 6 years deep that experience doesn’t mean you’re ahead or better than another.

Third, take pride in what you do. Your career is something to shine a light on and show people. Own the fact that you work in support. Don’t sell yourself and your talents short. If you’re not confident in the value of what you do then why should someone else be? Pride in your work is the foundation for your career; and that’s true whether you want to build and manage a team, help people everyday, perfect your technical writing skills, or any other career path support provides.

So be proactive. Maintain a healthy perspective, especially around measurable results. And have a sense of pride in your craft. Those are the steps I’d like you to take toward your career in support.

If that sounds interesting to you, we’re always hiring for people passionate about support. And if you have questions, feel free to get in touch.